THERE’S a well-known way to decide what to do, based on what’s urgent and important. It’s called the Eisenhower Box – and I think it has multiple flaws. Here’s why, and how to turn it into a new, better way to tackle tasks and plan your day.

(A short version of this article has less detail & wit.)

What to do?

The great problem of life is what to do. Your life consists of millions of decisions large and small, from making coffee to running for President. Which should you do, and when, and how?

There’s all the things to be done at work and home, constant demands and distractions, unfulfilled ambitions at the back of your mind… and barely time to think, let alone get through all this stuff.

Happily, a box has been invented to help you out. A bit like an Amazon Echo – but made only of paper & ink – it not only tells you how to deal with everything on your plate, but magically makes some of it disappear.

If it sounds a bit too good to be true, you’re right. But before we get to that, and a better solution, what is this box, exactly?

The box

The Eisenhower Box (or Matrix) is a diagram for deciding how to deal with tasks, based on whether they’re urgent or important. Invented by Stephen Covey in his bestseller The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, it was later named after US President Dwight Eisenhower, who once said:

“I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The

urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.”

The point being, people spend too much time on urgent-seeming but unimportant distractions, instead of on important, non-urgent matters – such as planning, people, and future opportunities. Short-term trivia divert you from what really counts.

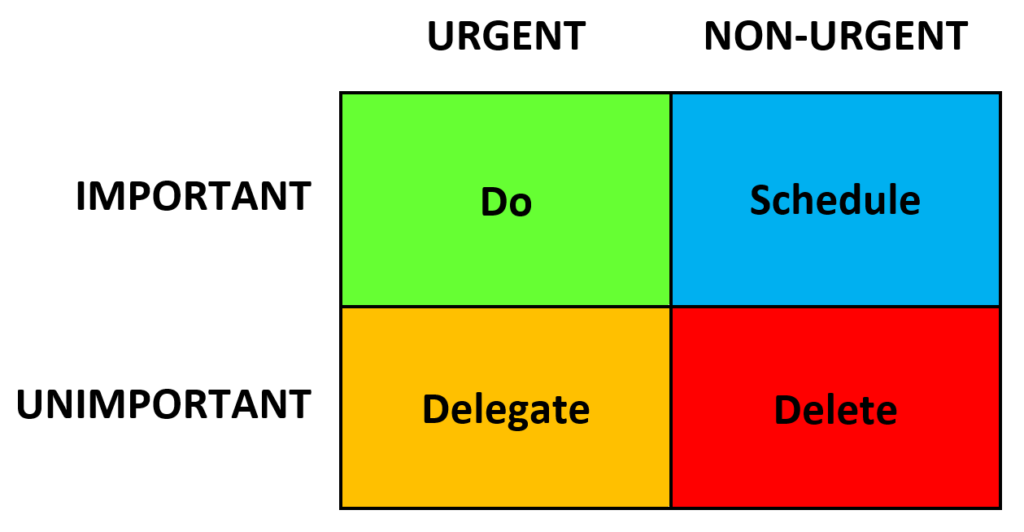

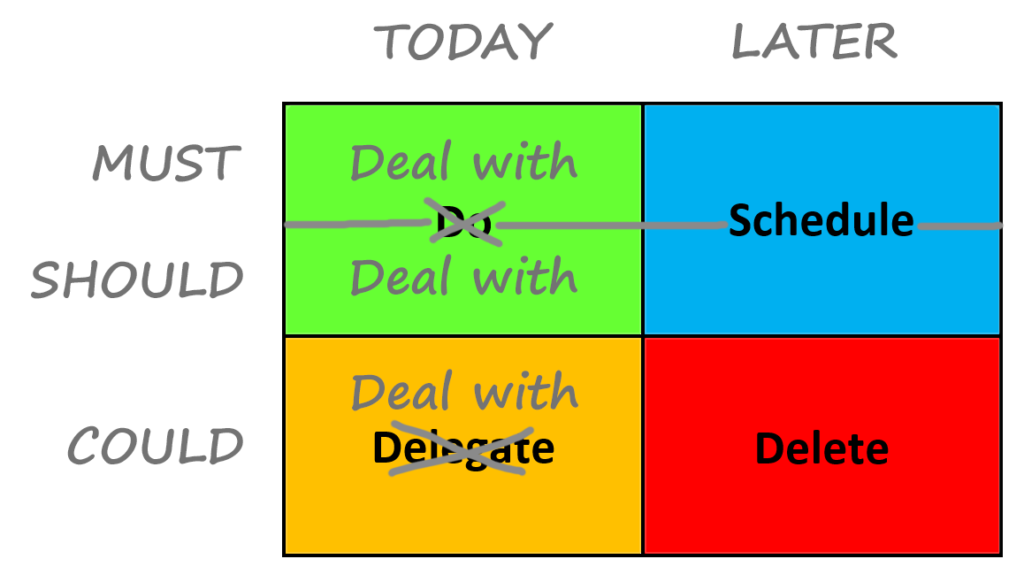

To solve this, the Eisenhower Box tells you what to do with each task that happens along, based on whether it’s important or urgent:1

The kind of tasks that end up in each cell, starting top-left, are:

- Important & Urgent (green): things that need action ASAP, such as important meetings/calls/emails, tight deadlines, and crises. They’ve got to be done, so – like the box says – you’d better Do them.

- Important & Non-Urgent (blue): big-picture, longer-term, proactive things you don’t do enough of – planning, identifying opportunities, talking to people, recruiting, training, self-improvement, etc. They are rarely pressing, but help prevent the scrambles and crises of the stressful green cell; indeed, Covey (the box’s inventor) says they’re the most crucial, yet neglected, tasks of all. So Schedule them in your calendar, to avoid procrastinating them for ever.

- Unimportant & Urgent (orange): unnecessary meetings, phone calls, interruptions, and similar needless demands from others. These grab your attention, so are easily mistaken as important – but you have better things to do, so Delegate these tasks to others.

- Unimportant & Non-Urgent (red): total time-wasters, such as pointless emails & business trips, aimless web browsing & social media, and other displacement activities that avoid real work. You know you shouldn’t be doing these, but go ahead anyway – because they’re easy or enjoyable, and feel a bit like work. Wise up and Delete these things entirely.

So, for anything on your to-do list – whether work or personal – just toss it into the box, and out falls how best to deal with it. You’ll end up spending quality time on what matters, while delegating and deleting less important stuff. And everything will go swimmingly.

All very plausible – yes?

Well, close examination shows that this is half-right, but also half-wrong. And being half-wrong, it only half-works. But I won’t rip up the Eisenhower Box into little shreds, as we can patch it up and relabel it to make a better one.

Let’s think outside the Box by questioning each of its labels in turn:

Urgent / Non-urgent

There’s certainly something special about urgent tasks. The dictionary defines ‘urgent’ as ‘requiring immediate action’. How could this not be crucial for deciding what to do?

Alas, Covey uses the word both for things which really are urgent – like an angry phone-call from a major customer, or a crisis meeting – and those that merely seem urgent, like a phone-call from an insurance salesman, or a toddler shrieking for ice cream.

The former do require immediate action, but the latter merely grab your attention; they may involve urging, but they are not urgent. Calling both ‘urgent’ blurs the crucial distinction; it fails to tell us which is which, and how to treat them. In fact, the real difference is that the former things are important, and the latter unimportant.2 But the box already makes this distinction via its rows; classifying all these tasks as Urgent doesn’t help one jot.

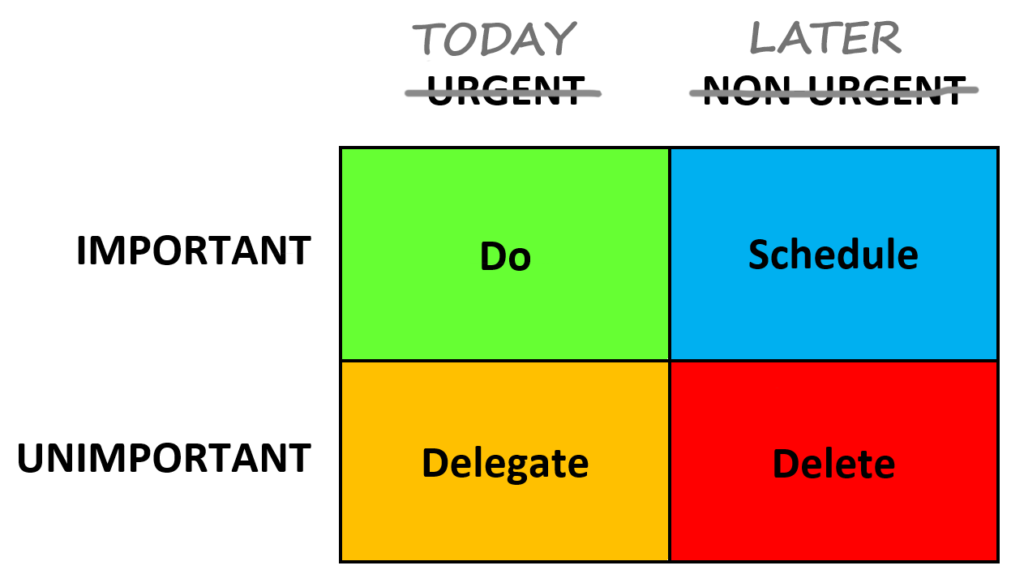

However, there’s another aspect of urgency, and the clue is in the dictionary definition: the word ‘immediate’. How soon is ‘immediate’? Be specific! Well, if you make a to-do list each day, it’s useful to distinguish what needs doing today from what can be put off until later, e.g. tomorrow. For example, collecting the kids from school must be done today – it can’t be postponed; whereas collecting a jacket from the dry cleaners can be done tomorrow or next week, if you don’t need it yet.

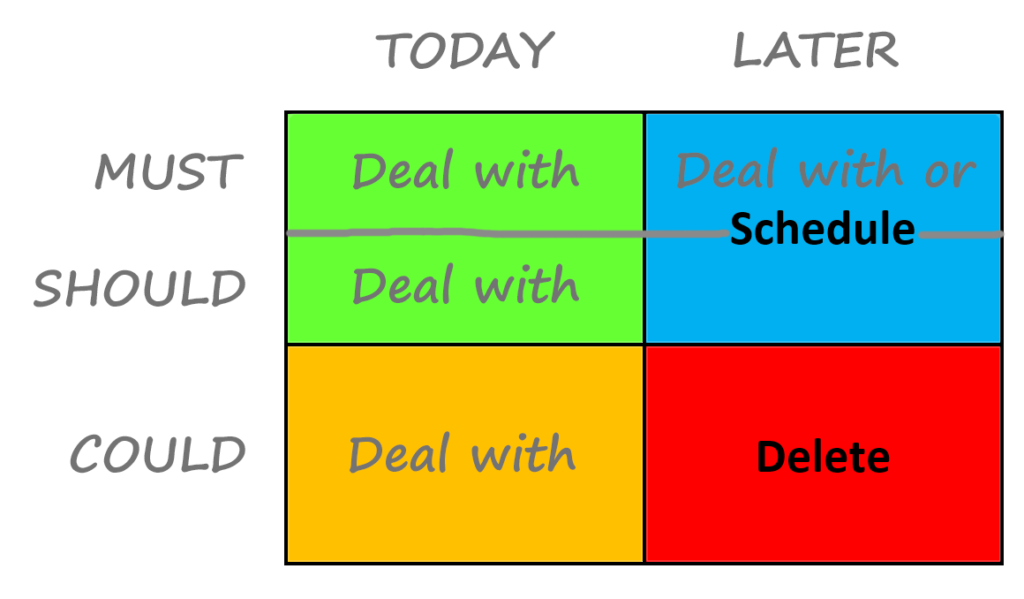

So, we can improve the Eisenhower Box by replacing Urgent/Non-Urgent with this better distinction – Today versus Later:

Important / Unimportant

The box is absolutely right to identify importance as important. But we can do better.

Suppose you have a crucial project to finish today, and also a meeting you ought to attend but which isn’t essential. You’d better skip the meeting and get on with the project. Both are important, but the project is a ‘must’, and takes precedence.

Some things are more important than others; importance comes in shades of grey. But the Eisenhower Box only distinguishes black and white: Important and Unimportant. As far as it’s concerned, the project and the meeting are equally important; it can’t tell you which to do.

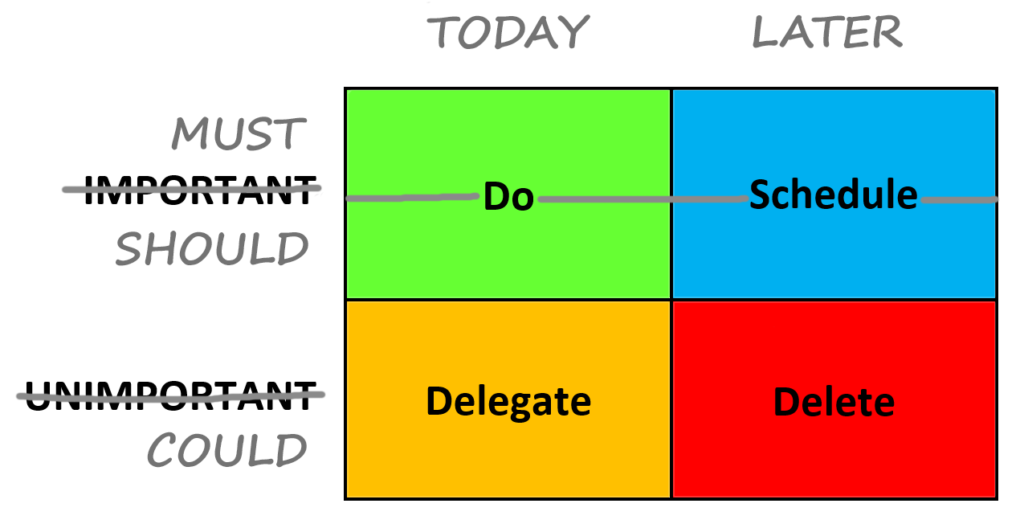

Far more useful is to distinguish three degrees of importance: things you must do, come what may (like the project); those you should do, which are preferable but inessential (like the meeting); and those you could do, but don’t matter much (like a lot of email). The must/should/could distinction is also easy to understand – we use these words all the time.3

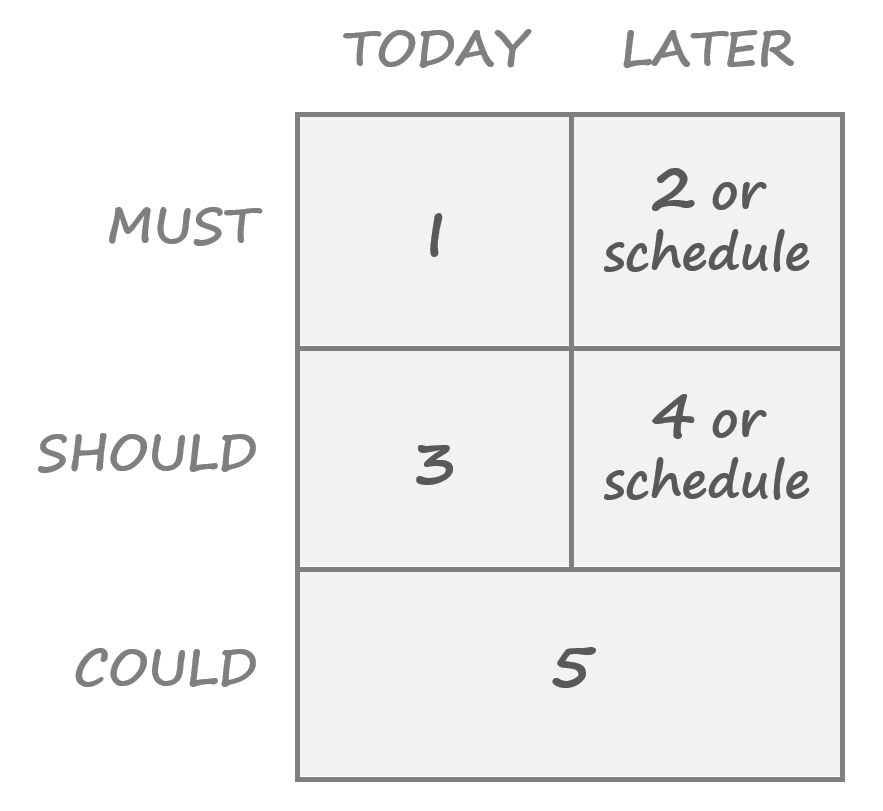

We can adapt the box to use them by splitting the Important row into two – Must and Should – and renaming Unimportant as Could:

So now the top left half-cell is for things you Must do Today – like finish the project, or collect the kids from school – and top right, things you Must do Later, such as your tax return (not due for three months). Must means that if a task isn’t done, you risk disaster; and Must Today means you risk disaster if the task isn’t done today.4 Hence, you will definitely do 100% of Must tasks if at all possible.

In the new row below the Musts are things you Should do Today – like attend the useful but inessential meeting, or eat lunch (though you might skip that too if necessary) – and things you Should do Later, e.g. buy a faster laptop, even though your current one is OK for now.

Finally, the Could row contains everything else on your to-do list.

Do / Delegate

The Eisenhower Box is quite right to recommend delegating. It’s inefficient, indeed impossible, to do everything yourself. So it tells you to do the Important Urgent tasks, and delegate Unimportant Urgent things to others. As the saying goes, “if you want a job done properly, do it yourself”.

But should you?

For many important tasks, you shouldn’t do them yourself – you should delegate them. If you’re on trial for bank robbery, don’t try to conduct your own defence – delegate that to a lawyer. Nor should you do your business’s accounts yourself; mistakes could lead to fines or a tax investigation. Delegate it to an accountant instead.

Conversely, many unimportant things aren’t worth delegating. To hang a picture on the wall, you could get a handyman in, but it’s probably not worth the hassle and cost; if you have a hammer and nail, just do it yourself. Prince Charles has a valet who squeezes toothpaste onto the royal toothbrush for him; but it’s not worth hiring your own valet for this – squeeze your own toothpaste.

And for many tasks, whether you delegate or not depends on how busy you are. If you’re a CEO, you usually meet big customers yourself; but if a major crisis hits, you send your sales manager in your place. When you have friends round, you usually cook your favourite pizza recipe; but if you have to leave work late, you order a pizza delivery instead.

So the reality is, you should Do some important tasks, and Delegate others; Do some unimportant tasks and Delegate others. The box can’t tell us which. Hence we should replace these words with a single phrase that covers both – ‘deal with’:

Dealing with a task means getting it done – either yourself, or by someone else. Which could be anyone who’s suitable and available: a junior, your boss, a contractor, partner, friend, etc.

The decision whether to delegate actually depends not on importance, but on what is best use of your time. For an important task for which you’re best suited – e.g. a meeting with a big customer – your time is best spent doing it yourself. Unless, that is, there’s an even better use of your time, such as handling a major crisis.

Similarly, you like making pizza, but if working late is a better use of your time, do that instead, and delegate the cooking to your local pizzeria.

You may handle the meeting better than anyone else, or make better pizza than the pizzeria, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you should do it – if you have better things to do.

Schedule

(Sometimes labelled ‘Do later’, ‘Decide’, or ‘Plan’.)

What about tasks in the blue cell, that we Must or Should do Later? The Eisenhower Box suggests we schedule them for some future date, which is certainly better than ignoring them. But there are other ways to handle these tasks – like, actually do them today, or at least make a start.

For if the task is a long one, i.e. a project, it’s best to start on it sooner than you might optimistically schedule. And the longer, harder & more important the project, and the firmer the deadline, the earlier you should start. Unknown unknowns and emergencies often cause delays – and even without them, you can’t be sure you’ll finish on time. I have even heard of occasions on which things were left to the very last minute, but then turned out to take longer than expected.

Making even a small start today, such as a few minutes thinking, researching or planning, may reveal important information – e.g. that the project is much harder than you thought, or needs someone or something you hadn’t anticipated.

Alternatively, it may make sense to delegate the task, or some part of it. In which case, the sooner you do so the better, so whoever you’re delegating to can fit it into their schedule. They may be busy too.

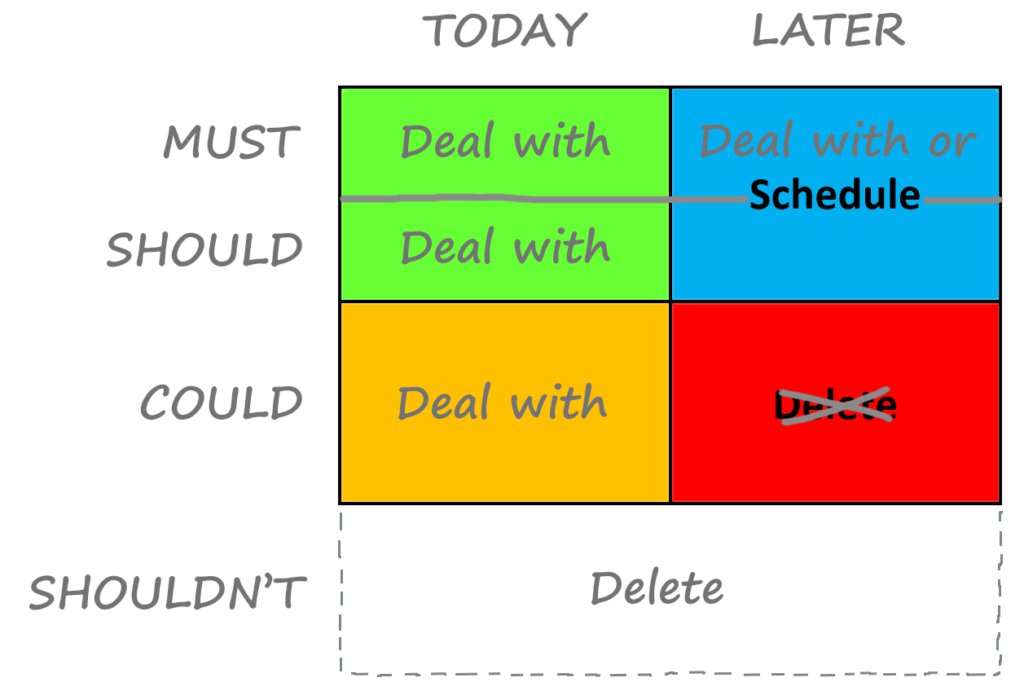

So for blue-cell tasks, as an alternative to scheduling them, also consider doing, delegating, or at least starting on them today. That is, ‘deal with’ them:

Delete

(Sometimes called ‘Eliminate’ or ‘Drop’.)

Some things really are a waste of time, and the Eisenhower Box is right to try to stop us doing them. But does it identify them correctly?

Just as the Important row combines two degrees of importance – essential (Must) and merely preferable (Should) – the Unimportant row hides two degrees of unimportance: things worth getting done if possible, and things never worth doing. Like aimless web surfing, social media (in work time), pointless emails, and other wastes of time.

However, the latter aren’t so much tasks you Could do, as things you shouldn’t do; they really belong on a separate ‘Shouldn’t’ row below, for stuff you actually should Delete:

That said, in practice we don’t need this extra row, because you already know you shouldn’t do these things. It’s not as if ‘watch cat videos’ is on your to-do list, and you need the box to decide between that or some crucial project; you already know the answer. So we can forget about total time-wasters – just don’t do them.

Apart from those, anything else you Could do might be worth doing someday – so there’s no point deleting them.

For example, suppose your bathroom is looking a bit shabby, and you’re wondering whether to repaint it. This is something you Could do Later, e.g. next weekend; but on the other hand, it hardly matters. Faced with this dilemma, you may be tempted to be decisive: either actually do it next weekend, or forget the whole idea – Delete it.

But if you don’t repaint the bathroom next weekend, nothing is gained by deciding never to do it. The task can just loiter around the bottom of your list until you have nothing better to do, if ever. For the opportunity may arise, e.g. if you get painters in for some other job; or the situation may change, if in a year or two the bathroom looks much worse, or you want to sell your house, so decide to paint it after all. Why Delete tasks if you might end up doing them anyway?

This does mean your complete to-do list will include lots of minor things that may never get done.5 Accept this. You won’t ever finish your list – and that’s OK. For if there were nothing left to do, what would there be to live for?

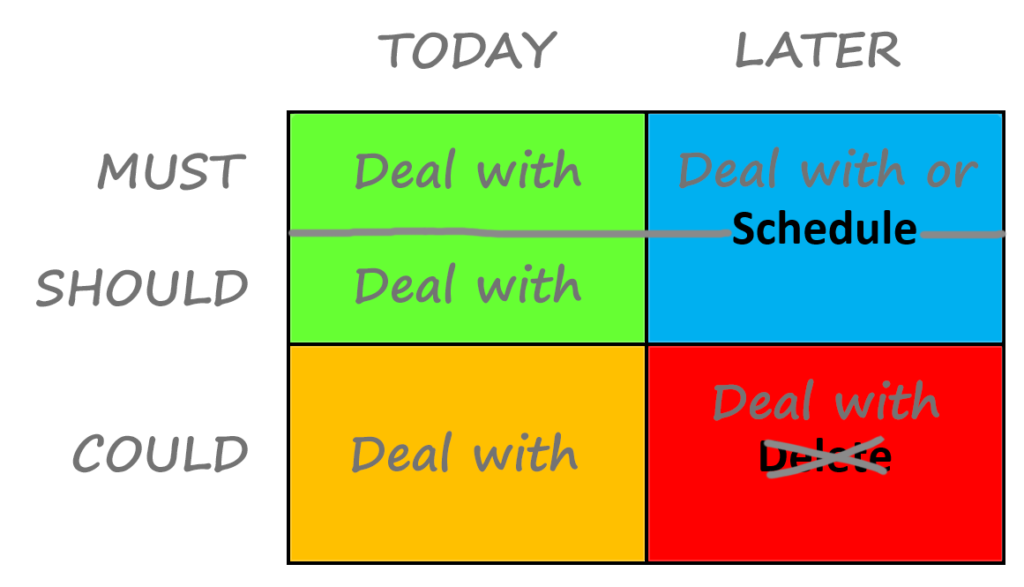

So, we shouldn’t have a Shouldn’t row; let’s delete Delete; and instead, make anything you could do later just another task to Deal With, if you ever get around to it:

Note the phrase ‘get around to it’. Unimportant tasks loiter at the bottom of your to-do list, seldom getting done, because you almost always have other things to do first.

So what order should you do things in?

Prioritizing

The Eisenhower Box kind of assumes you’ll have enough time to do what it tells you. But what if you don’t? Scheduling should be quick enough, but there may not be enough hours in the day to Do all the green tasks, let alone Delegate the orange ones (as delegating can take time). Something must give; but what?

If we can work out an order of priority for tasks, then if you don’t complete them today, at least you’ll have done what matters most. We can figure out the order like this (bear with me):

Must Todays must by definition be dealt with today, come what may – so do them first of all. Doing anything else increases the risk of not completing them.

Should Todays are more important than Coulds, so should be done before them. Doing Coulds instead of what you Should be doing is a symptom of ‘busyness’ – merrily filling your day with minor tasks that aren’t a waste of time, but aren’t much use either.

A harder conundrum is: which is higher priority, Should Today or Must Later? The pressing meeting, or the crucial long-term strategy that can wait? Well, if you do Should Todays first, you may not get through the Must Laters on your list. And if this happens day after day, some Must Laters will be procrastinated indefinitely, and you’ll miss crucial deadlines and opportunities. Whereas Should Todays are merely desirable. Hence it’s best to deal with Must Laters before Should Todays; and if you’re too busy to work on a Must Later, at least you can schedule it in seconds.

For example, suppose your business relies on selling just one product. At some point you must come up with a new one – a task you Must do Later. But you’re so focussed on your current product that your to-do list is full of Should Todays – reply to enquiries, order stock, issue invoices, etc. If you keep dealing with these every day rather than even thinking about a new product, a sudden competitor to your current one could make you go bust before you can say ‘mañana’. But by prioritizing Must Laters before Should Todays, you’ll either start planning your new product today, or at least put a date in the diary to do so. It prevents endless procrastination.

And by the same reasoning, Should Laters are higher priority than Could Todays – or you may keep postponing important things by filling your days with trivia.

Putting this all together, the optimal order to tackle tasks turns out as:

- Must Today

- Must Later

- Should Today

- Should Later

- Could Today/Later

(though there are exceptions, covered below).

With Coulds, it’s hardly worth distinguishing Could Today from Could Later. The timing of Coulds usually doesn’t matter much, because the task itself doesn’t matter much, and you probably won’t get round to it today anyway. Hence we can combine them into a single Could category.

Hopscotch

Now let’s redraw our reworked box more neatly. We can lose the colours, and replace ‘deal with’ with the above numbers for the order to do those tasks in:

For whimsical reasons I’ll call this new box and method Hopscotch. Use it like this:

Plan your day

At the start of each day (or the end of the previous one), go through your full to-do list and appointments, and ask yourself which things you must deal with today, must deal with later, should deal with today, etc. Perhaps label them MT, ML, ST etc. as you go. If you have lots to do, selecting just these top three categories should suffice; but if you include Coulds, pick just the most important ones, as chances are you won’t get round to them today anyway.

Copy these tasks to make a separate to-do list for the day – your day plan. Then put it into the Hopscotch number order: Must Todays first, then Must Laters, then Should Todays, etc.

Within each of these categories, put tasks into roughly descending order of importance; if unsure, also consider which need doing sooner. It’s often unclear whether something counts as a Must or a Should, or a Should versus Could, but that hardly matters if tasks are ordered within each category too.

You can then move tasks around for a few reasons:

- If it’s at a fixed time (e.g. a scheduled meeting/call), or must be done after something else (e.g. it’s awaiting approval), move it to about where in the order you expect to do it.

- Put related tasks together to increase efficiency, e.g. ones from the same project or in the same location. If you Must go to the dentist, you may as well buy some milk nearby to save a separate trip, even if that’s just a Should. (But think twice about moving Coulds earlier.)

- Move a quick Should Today task earlier if it’s best done ASAP. E.g. by sending a one-line email first thing, so the recipient can work on it today.

- All that said, if your Must Todays might take all day, don’t do anything else until they’re finished.

It’s easiest if your full to-do list is in software – even good ol’ Microsoft Word will do – and you keep it in rough order of importance.

Using your day plan

Now, down to work. Deal with tasks in the planned order; don’t cherry-pick ones you feel like doing. Remember that ‘dealing with’ a task can involve getting someone else to (delegating), depending on what’s the best use of your time, and who else could do it.

Whenever a new task arrives during the day, again ask yourself whether you really must deal with it today. If so, do it next, or add it to the Must Todays in your plan; if not, you can probably just leave it to consider tomorrow.

You may well not get through everything by the end of the day. That’s fine – leftover tasks can go on tomorrow’s plan. But when you compile it, reconsider whether leftovers are still Must/Should/Could or Today/Later, as their priorities may have changed; they may not even be worth including.

Simpler version

Hopscotch is pretty simple, with just one more cell than the Eisenhower Box. But for something simpler still, we can combine cells 2 & 3, and 4 & 5, to make this minimal method that doesn’t even need a box:

- Start with tasks you must deal with today (unless they have to be done later in the day)

- Then, tasks you should deal with today – the most important first, especially working on or scheduling things you must deal with sometime

- Finally, deal with anything else, in order of importance.

Try it!

When it comes to productivity, there’s one thing better than reading, and that’s doing. So try Hopscotch for a few days, and see how much more you get done. Go on, try it – right now!

Or if you’ve only got a spare minute, try the simpler version – or just the first step: What must you deal with today?

P.S.

Hopscotch is better than the Eisenhower Box, but by no means solves everything. For example, there are issues with deciding how important things are, tasks without clear deadlines, different time horizons, and considerations beyond importance and timing.

But I’ll write more about these soon. Or when I get around to it.

P.P.S. If you found this article half-interesting, please scroll to the bottom to share or subscribe.

[1] Stephen Covey did not propose the one-word actions for each cell, which seem to have been added by later writers, and are an oversimplification of what he says; for instance, he did not claim Unimportant Urgent tasks are the only ones you should Delegate.

[2] Hence there are no Unimportant Urgent tasks, and nothing belongs in the orange cell. Anything truly urgent – that requires action – must be important, and so goes in the green cell.

[3] Some people label three degrees of importance A, B, C, or 1, 2, 3 instead; but these are arbitrary, meaningless symbols, hence liable to be used inconsistently.

[4] This doesn’t mean this is a Must task which you have merely chosen to do Today; it’s an objective deadline, e.g. for completing the project, or collecting the kids, after which things will probably go pear-shaped.

[5] Could Laters are like ‘Someday/Maybe’ tasks in David Allen’s Getting Things Done system: Someday = (much) Later, Maybe = Could. He proposes keeping them in a separate list, though in reality they’re just the bottom of one big to-do list.